As we progress through life, we must inevitably navigate through crossroads, moving down the path of life and necessarily leaving opportunities behind. At each moment when the choice is made, a path goes on unrealised. But more than this, the person you may have been had you taken that path fades into non-existence. It is strange to think about the mourning of a person who has not yet existed, although we do do it. We mourn the loss of a child who had life still left to live, no least because of the fact there are times ahead they’re going to miss. The mourning from an unrealised path differs from a child dying in both quality and quantity, but mourning for the future is common to both. For ourselves, we often attach ourselves to a vision of who we may be in the future. When we make a decision that forces us down a certain path, that future version of us is sentenced to an unrealised existence.

The situation of a forgone path of course exists within the bounds of controllable, as well as uncontrollable circumstances. Perhaps a chance accident occurs, and we are rendered without a leg. The future we imagined running marathons or playing football in now significantly changed. In addition to the direct pain and shock of the situation, this is likely to account for some significant part of the distress associated with significant and uncontrollable life events. What is on the other side may be unexpected, and on balance, it may even be good. The proverb of the Chinese farmer offers some insight into this line of thinking:

A farmer and his son had a beloved stallion who helped the family earn a living. One day, the horse ran away and their neighbours exclaimed, “Your horse ran away, what terrible luck!” The farmer replied, “Maybe so, maybe not. We’ll see.”

A few days later, the horse returned home, leading a few wild mares back to the farm as well. The neighbours shouted out, “Your horse has returned, and brought several horses home with him. What great luck!” The farmer replied, “Maybe so, maybe not. We’ll see.”

Later that week, the farmer’s son was trying to break one of the mares and she threw him to the ground, breaking his leg. The villagers cried, “Your son broke his leg, what terrible luck!” The farmer replied, “Maybe so, maybe not. We’ll see.”

A few weeks later, soldiers from the national army marched through town, recruiting all the able-bodied boys for the army. They did not take the farmer’s son, still recovering from his injury. Friends shouted, “Your boy is spared, what tremendous luck!” To which the farmer replied, “Maybe so, maybe not. We’ll see.”

The unpredictability of the time frame within which we assess the outcome of a situation plays a pivotal role in whether we see it as favourable or not.

One other factor divides controllable against the uncontrollable pivot point, that of control itself. When the situation is in our control, we are liable to regret. We are the agent responsible for the direction taken. Regret exists as an important consideration in addition to the outcome itself. The fear of regret itself may play an important role in stalling our decision making around key life choices. Regret may itself be an inevitable feature of making such decisions, as by making a choice we necessarily forgo some other choice, which no matter how marginally positive it may be, we are liable to regret forgoing.

The ‘path’ analogy to decision making in life does require some further nuance. When choosing a path, we ideally take one which leads to a life in which we’re realising some sense of self we currently perceive as desirable. There are however two main moving parts in this equation:

- The path itself is likely to take unexpected turns, be liable to change and open to some degree of malleability, i.e. paths are rarely straight, narrow and unchangeable

- What we see as desirable is likely to change over time

Point 1 is exemplified well by the proverb of the farmer above. Ultimately, how we view the outcome of a choice depends upon the point at which we view the choice. If we decide to train for a long and challenging hike, we’re likely to encounter early mornings, difficult times and ultimately that at any one moment it may be preferable to stay at home and enjoy a movie, than get out and train. However, from the point of view of the person who has completed the hike, the benefits stand tall above the cost of the journey, and we can be ultimately glad we made the decision to do it.

Point 2 is more difficult to deal with. How are we to make value judgements if we’re inherently uncertain about the values upon which the judgements are based? The temptation may be to err toward optionality, making a decision that allows for maximal flexibility so that future decisions have a wider array of possibility, and account for likely future changes in values. But this isn’t particularly helpful, as meaningful paths can often require some investment of time over a prolonged period, and whilst preferring not to ‘lock in’ to a path early is understandable, it does relieve from the fact high value options exist down narrow paths. Similarly, ignoring the fact our values are likely to change over time is not productive, it’s important to attempt to anticipate the trajectory of value changes and plan accordingly. Unfortunately there doesn’t seem to be a reliable or concrete means of doing so, so where to from here?

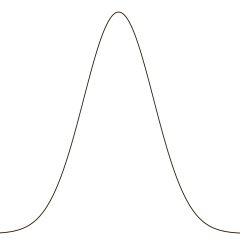

A reasonable approach seems to be attempting to project your value set accounting for the phenomena of regression to the mean. Are there important life events you foresee arising in the next decade, or two? How will these alter your values? This is a simple and relatively intuitive approach. In addition, are you particularly on an upper or lower bound for a particular trait at the moment? Perhaps conscientiousness at work is currently a priority, and you rank somewhere near the top percentiles of the bell curve. It would be prudent to assume that your willingness to continue valuing conscientiousness at work will regress to the mean over time as your values shift. Another reasonable guiding principle is to approach the direction of one’s life with curiosity and a willingness to change one’s mind with the availability of new information or understanding. Perhaps a framework of thought and value takes some years to come to, but is sufficiently convincing to err you toward a new path in life. In order to begin down said new path, new foundations and groundwork may need to be laid, but if you’re convinced of your value set, this should just be a matter of doing the work.

“He who has a why to live for, can bear almost any how”

Friedrich Nietzche

The course of life is unpredictable, uncertain and marches forward with unrelenting fortitude. As humans we aspire to shape our lives in certain way, to mould our experience and perceptions of self. In doing so, we must forgo the opportunity to embody certain versions of ourself, to pursue the life we ultimately end up living. Navigating such a life is difficult, but there is nothing more human than doing so. The beauty is in the struggle.